Translated by Katrina Hassan

The day of the year doesn’t matter, neither does the weather. Even if it is pouring rain, they are always there. From dusk until dawn, breaking their back. Their bodies, a work tool, and their means of survival.

It doesn’t matter if they think or feel. If they ask themselves what time it is. A clock, for the exploited worker, never stops ticking. It matters not that they have blisters or a toothache. No matter if a relative died, or if their child is born. They are always there. Breaking their backs.

They are never seen as a person. On the contrary, they only get in the way as you walk through the street market’s corridors. There is always someone that shouts at them or gestures in disgust as they get a whiff of their sweaty, working bodies.

There are also those who stereotype them and think of them as thieves. They rarely wear shoes. If so, they are torn. In winter, their feet are tired and are the cradle of ringworm of the season.

Their shirts are also torn and worn bare. It is probably the only shirt they own, and that is, to be worn for work. That is not important, for they are not important. One, two, three, four hundredweights carried on their shoulders.

Then, they walk-run through the busy corridors of the market that are always teaming with customers. Behind them, the owner of the merchandise follows. If only the owner had a whip to smack their legs, so they could go faster, just like a beast of burden.

They have become an essential part in sustaining, on their shoulders, classism and exploitation from a society that sees the pariah much like a rodent from the sewer.

Young men whose bodies have aged with sheer tiredness. Old men that run – walk, by the pure automatic movement of the routine. They are worn out, their dream shattered. Their teeth, without a doubt, have been lost through the market aisles. Lost to anyone, who in exchange for a coin or a kick in the ass, has exploited them. Their lives have passed them by through hundredweights and baskets hauled on their backs. Who looks out for them?

Without a doubt, they must have had dreams. Maybe they still have them? Go to school? Graduate from university? Have their own business? Write a book? Be a doctor? A teacher?

Or, simply, have a roof over one’s head, maybe a pair of shoes. To have a bit of land to cultivate. To drink a cup of coffee. To sleep on a mattress. What do pariahs from the sewer dream of? Many a times, when they walk-run, their shirts get drenched in liquid that seeps from the loads they carry.

It can be beef blood, seafood, rotten tomatoes, ripe fruit, putrid flowers. Stenches mixed with sweat and ire that end in tears that no one wants to see. The pain of a pariah is invisible to a society that exploits those that have the least.

How are the nights for these load carriers? The few hours they sleep. How might they be? Do they rent a room in a cheap guest house? Do they sleep in the corridors of the market, without any cover, outdoors? Do they sniff glue or thinner? Do they get drunk with cans of alcohol? Do they paint masterpieces? How are the nights of the load carrier? Do they write poems on loose sheets of paper? Where do they shower? Do they have any belongings?

The majority of load carriers come to the city from villages. They usually don’t have family in town.Do they have any belongings? What is inside their backpacks? They arrive believing the big city has opportunities to develop themselves.

The city is the place where they’ve been told that dreams come true. Most of the load carriers are indigenous people that only speak their mother language. They have been forced to migrate. This helps others exploit them even more.

They come as children and rot between all the walking-running with the bulk they carry over their tired shoulders. All this through the corridors of the outdoor markets. This, in towns that can only offer contempt, exploitation and discrimination. The same way they arrive, breaking their back, they die. Invisible, like rodents in the sewer.

If you share this text in another website and/or social media, please cite the original source and URL: https://cronicasdeunainquilina.com

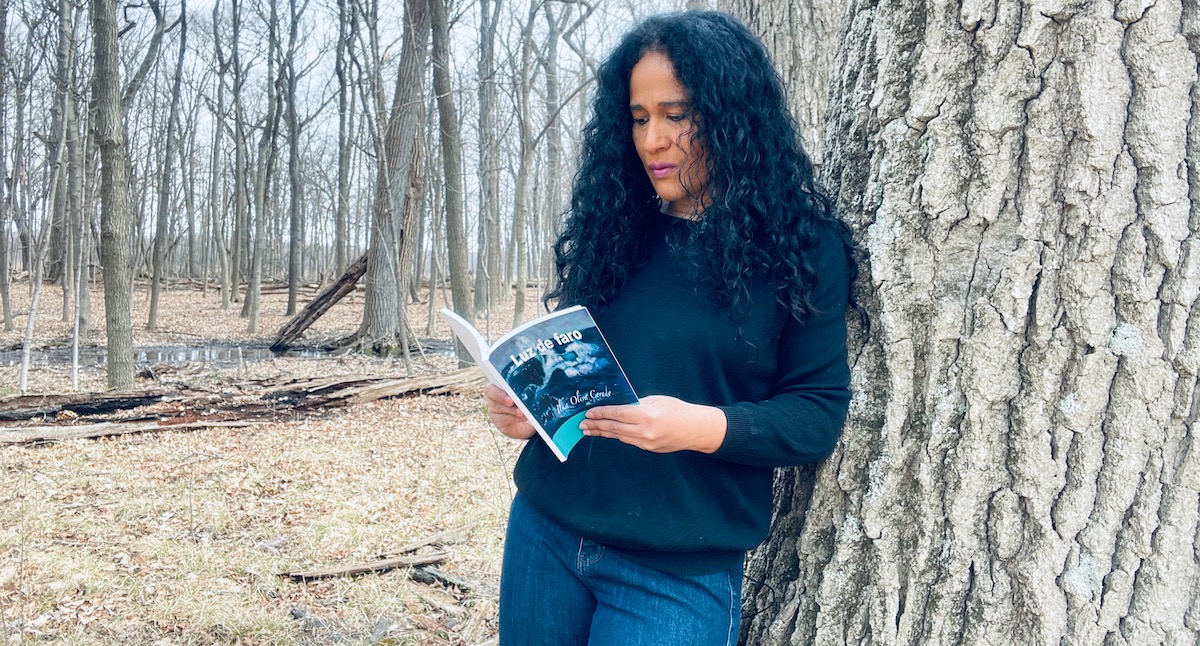

Ilka Oliva Corado @ilkaolivacorado