Translated by Katrina Hassan

It is June, around lunchtime and the heat is infernal. I observe the labourers from the window facing the street as I go upstairs at my place of work. Their bodies are drenched in sweat. With a pick, they open the earth to dig a trench all along the side the house in order to fix the plumbing. In the morning, the owner of the company, a Polish man of about 60 comes to show his face. He gets in his latest model double traction pick up truck and leaves.

I serve two glasses of ice water and ask the workers how the heat is treating them. “Do you live here?’ They asked surprised, after seeing a Latin American woman . “No, I work here. I am the maid. Actually the nanny, but you know, that’s the same thing.” I say as I hand them the water.

They happen to be from Guatemala, from the East. They speak Spanish with difficulty. It is an uncle and his nephew. The uncle is 35 years old, he came here 18 years ago. His nephew is 16 and arrived 6 months ago. They place the glasses near the trench and keep digging, one with the pick and the other with a shovel.

I see the nephew struggling with the shovel. I am thinking he should be at school instead. His uncle reads my mind and says “He followed my son here. My son came here one month before him. They grew up together. They are thick as thieves. My son didn’t want to come with me, he went with his mom. This one here came to live with me. I basically raised him; his mom being a single mother. This boy’s dad also came to live here but was never heard from again. They say he is in California and that he has another family. Next week my nephew goes to join my son because they cannot be apart. Besides, he can’t handle this kind of work. Anyway, he came to see me, and my son didn’t.”

“Your son must have his reasons” I say. “You went far away and you were not physically present.” “But I called him on the phone every day.” Antonio says. “I tried to be as close as I could but the distance prevented me from doing so. If I could’ve travelled back home, that would’ve been a different story.

Antonio is 35 years old. His skin is sunburned. He wears a t-shirt with a button up long sleeve shirt over it, to cover his arms, a baseball cap to cover some of his face, thick soled shoes and rolled up canvas pants. José, the nephew, is wearing a t-shirt that would be all the rage in Guatemala, but is now covered in dirt. His jeans are very different than his uncle’s. They’re definitely from a different generation.

“The life of the poor is hard, isn’t it Antonio?” I say while I lean on the wall of the house. I can feel the summer heat on my skin. He says “Look” without letting go of the pick, “I came here as a kid, having left a 6 month old baby. I didn’t want my kid to live in the same poverty as me. I wanted my wife and baby to have a house, running water, shoes and food on the table. I wanted my kid to go to school. This is the reason I left. I wanted my kid to get an education, unlike me, who had to work as a child in farms with my family.”

“I have worked in all sorts of different jobs here. Even those that you can’t imagine. We get double discrimination here. One for being indigenous and not knowing how to speak Spanish, the other for not speaking English. I always get the heavy lifting in construction jobs because they think I am just a back to load. As if I do not tire, but I do! A lot! I sent money back home however I could, every week, all these years. I have worked three jobs ever since I got here. I never stop. I work everyday in anything I can find. I am a jack of all trades. Some days I install bathrooms, roofs, gardening, anything really. I end up spent. I can’t even begin to tell you the humiliation I went through when I was trying to learn these trades. Nobody taught me. No one wants to teach you how to do these jobs. I learned all by myself, observing and by the eye.”

Like most undocumented workers, Antonio thought he would come here for a year or two. Then reality hits and he learns that it is not so easy to send money home. He need to have at least 3 jobs. By the time you learn a trade and mobilize yourself, at least 8 years have passed.

“In one apartment there lived 11 of us, all from my village. We all had left our families back home. We all tried to work together on jobs so we could help each other out with gas and have at least a little bit to eat.”

Antonio works for a Polish man, that only shows his face every now and then. He brings along his robust and healthy sons, to check on the jobs that the undocumented do for him. People like Antonio and his nephew José. The ones that do all the dirty work are the undocumented Latinos.

“I build them a house and it was all in vain because they came here to the US to suffer like me. My wife ended up picking fruit and vegetables. She goes from state to state chasing the picking seasons. She has no home. She lives with all the other field workers in groups and they sleep in the fields in tents. Three weeks here, a month there; they travel the whole country like this. I am a failure. It was pointless to come here.” Antonio says. “Would you go back?” I ask. “No, only if I get deported. What would I go back for? All that I loved was destroyed”

There are thousands of people like Antonio. Forced migration destroys families for ever. Sooner or later migrants’ kids emigrate too, many on their own accord. Others go looking for their parents. When they find them they realize that they don’t feel a bond to these people who in reality are strangers. This is how they all end up living in separate places, like Antonio and his son.

Antonio repeats “I built them a house! Now she is out there picking fruit, as if I came here to sacrifice myself for that.” he leaves his pick aside and takes the glass of water and rests a minute. His nephew, who was listening all along with his head down, also stops for a moment.

“What do dream of doing?” I ask José. “The same as my uncle. Work hard so my kid can go to school.” he answers. “You have a son too?” I ask. “Yes” he answers shyly. José is only 16 years old. “I want to work for them to have a house. I want my kid to go to school and finish university. I want to save a little bit so I can open a business and go back.” he says. “Was the grass greener as people said on this side?” I ask. “No, nothing is like they said, everyone lies. The USA is nothing like what people tell you it will be.”

The story of Antonio is repeated with José. This is repeated a million times more. Forced migration is intricate.

Antonio mentions that he has been the only one to tell people the truth about coming over to the US as undocumented. Alas, necessity is enormous and for this reason, the young people of his village migrate and leave behind only grandparents. Parents and kids have gone North to lose themselves in the city.

I pick up the glasses and I leave them to work under the hot American sun. I start to go back to work, but while I walk, Antonio’s words chime in my head. “Here, we lose everything.” It is so true.

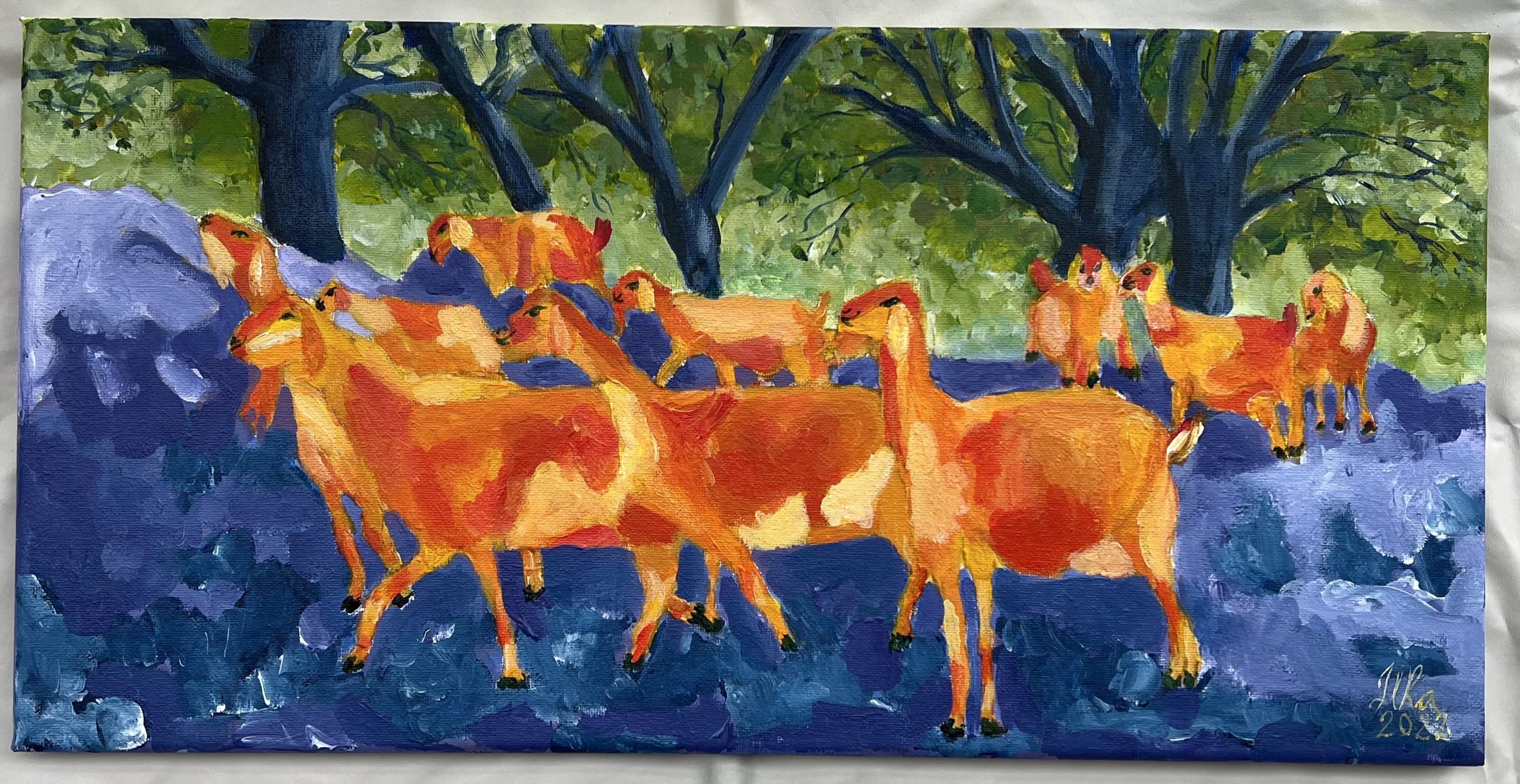

Stories like Antonio’s, his wife, son and Jose’s are common in this barn. This barn where the undocumented are like livestock that are getting taken to the slaughterhouse.

If you share this text in another website and/or social media, please cite the original source and URL: https://cronicasdeunainquilina.com

Ilka Oliva-Corado @ilkaolivacorado

20 de diciembre de 2018